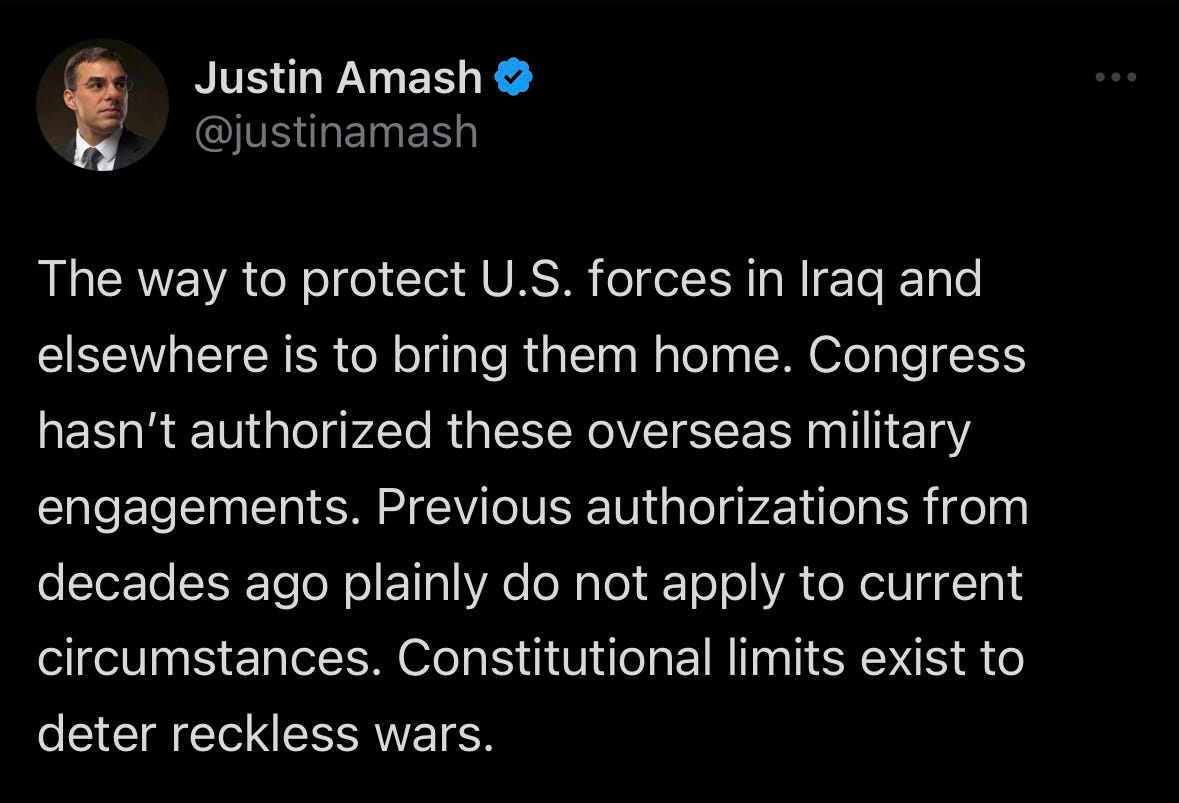

The other day I made an observation on X about how U.S. foreign policy continues to put American troops in harm’s way without any clear mission or commitment from the American people and their representatives in Congress.

While my post received overwhelmingly positive responses, there was predictable pushback from a few hawks who decried my view as “isolationism.”

Here’s why that criticism is totally disingenuous.

First, if not stationing troops in dozens of countries around the world constitutes isolationism, then the vast majority of nations on earth are isolationist. But we don’t call those countries isolationist, because that’s not what isolationism is.

Similarly, if someone refrains from stationing armed guards at dozens of neighborhoods around the city, we don’t call that person a loner. That’s just not what it means to be a loner.

Isolationism is a policy of not engaging with other countries. A person can believe in robust engagement (trade, cultural exchange, and more) with individuals and organizations across the globe—including government-to-government engagement—while opposing an aggressive military posture, which usually serves to isolate people. In fact, this belief in expanding the scope of human cooperation and rejecting coercive force is the general position of millions of Americans who are most opposed to isolationism: classical liberals and libertarians.

Second, the accusation of “isolationism” with respect to my post is really just a way to evade the constitutional argument. And evading the constitutional argument is an effort to evade the representational argument.

There’s no getting around the fact that Congress hasn’t authorized current U.S. hostilities in places like Iraq. As I’ve noted previously on X, the 2002 Authorization for Use of Military Force doesn’t authorize operations generically in Iraq for all time. It authorizes operations specifically against Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, a government that was defeated and dissolved a generation ago.

Likewise, as I’ve pointed out, the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force doesn’t authorize operations in or against Iraq, Syria, or Iran. It authorizes operations exclusively against the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks and those who harbored them.

The response that all U.S. military actions in the region are simply defensive—and therefore don’t require congressional approval—doesn’t hold water when American troops, weapons, and resources are placed deliberately into fields of combat. When a president inserts U.S. forces into known conflict zones, he understands well that there will be any number of provocations, including attacks on American bases or troops, that might then be used to justify U.S. retaliation, with hostilities potentially escalating rapidly into a full-blown war.

The Framers of the Constitution recognized the enormous danger of placing the decision to go to war in the hands of the commander in chief of the Armed Forces, the president of the United States. So they didn’t. Whether the United States enters war is a policy choice that the Constitution leaves to the legislative branch, Congress—the body whose membership is closest to the people.

There’s a lot of talk these days about saving “our democracy.” Is there a more important democratic decision than whether our fathers and mothers, our sons and daughters should have to risk their lives in hostilities overseas?

The bottom line is that even if one believes that bringing American troops home (or keeping them out of areas of high conflict) amounts to isolationism, it nonetheless remains a decision left to members of Congress, not the president. And congressional inaction on military authorizations—for any reason or no reason—can never justify unauthorized presidential action, because inaction, too, is Congress’s prerogative.